Law of India

Law of India refers to the system of law which presently operates in India. It is largely based on English common law because of the long period of British colonial influence during the period of the British Raj. Much of contemporary Indian law shows substantial European and American influence. Various legislations first introduced by the British are still in effect in their modified forms today. During the drafting of the Indian Constitution, laws from Ireland, the United States, Britain, and France were all synthesized to get a refined set of Indian laws, as it currently stands. Indian laws also adhere to the United Nations guidelines on human rights law and the environmental law. Certain international trade laws, such as those on intellectual property, are also enforced in India.

Indian family law is complex, with each religion having its own specific laws which they adhere to. In most states, registering of marriages and divorces is not compulsory. There are separate laws governing Hindus, Muslims, Christians, Sikhs and followers of other religions. The exception to this rule is in the state of Goa, where a Portuguese uniform civil code is in place, in which all religions have a common law regarding marriages, divorces and adoption.

There are 1221 laws as of May 2010[1]

Contents |

History of Indian law

Ancient India represented a distinct tradition of law, and had an historically independent school of legal theory and practice. The Arthashastra, dating from 400 BC and the Manusmriti, from 100 AD, were influential treatises in India, texts that were considered authoritative legal guidance.[2] Manu's central philosophy was tolerance and pluralism, and was cited across Southeast Asia.[3] Early in this period, which finally culminated in the creation of the Gupta Empire, relations with ancient Greece and Rome were not infrequent. The appearance of similar fundamental institutions of international law in various parts of the world show that they are inherent in international society, irrespective of culture and tradition.[4] Inter-State relations in the pre-Islamic period resulted in clear-cut rules of warfare of a high humanitarian standard, in rules of neutrality, of treaty law, of customary law embodied in religious charters, in exchange of embassies of a temporary or semipermanent character.[5] When India became part of the British Empire, there was a break in tradition, and Hindu and Islamic law were supplanted by the common law.[6] As a result, the present judicial system of the country derives largely from the British system and has little correlation to the institutions of the pre-British era.[7]

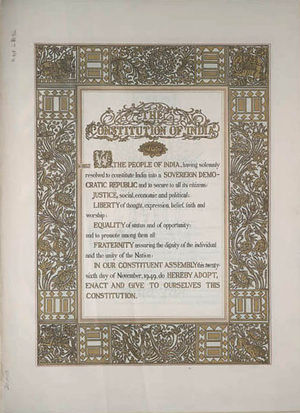

Constitutional and administrative law

The Constitution of India, which came into effect from January 26, 1950,[8] is the lengthiest written constitution in the world.[9] Although its administrative provisions are to a large extent based on the Government of India Act, 1935, it also contains various other provisions that were drawn from other constitutions in the world at the time of its creation.[9] It provides details of the administration of both the Union and the States, and codifies the relations between the Federal Government and the State Governments.[10] Also incorporated into the text are a chapter on the fundamental rights of citizens, as well as a chapter on directive principles of state policy.[11]

The constitution prescribes a federal structure of government, with a clearly defined separation of legislative and executive powers between the Federation and the States.[12] Each State Government has the freedom to draft it own laws on subjects which are classified as state subjects [1]. Laws passed by the Parliament of India and other pre-existing central laws on subjects which are classified as central subjects are binding on all citizens the country. However, the constitution also has certain unitary features such as the power of amendment being vested solely in the Federal Government,[13] the absence of dual citizenship,[14] and the overriding authority assumed by the Federal Government in times of emergency.[15]

Criminal law

Indian Penal Code formulated by the British during the British Raj in 1860, forms the backbone of criminal law in India. Jury trials were abolished by the government in 1960 on the grounds they would be susceptible to media and public influence. This decision was based on an 8-1 acquittal of Kawas Nanavati in K. M. Nanavati vs. State of Maharashtra, which was overturned by higher courts.

Capital punishment in India is legal but rarely used. The last execution was conducted in 2004, when Dhananjoy Chatterjee was hanged for the rape and murder of a 14-year old girl.[16] <-- Clarify stand on homosexuality [17] -->

Contract law

The main contract law in India is codified in the Indian Contract Act which came into effect on September 1, 1872 and extends to whole of India except the state of Jammu and Kashmir. It governs entering into contract, and the effects of breach of contract.

Labour law

Indian labour laws are among the most restrictive (for the employer) and complex in the world according to the World Bank.[18][19]

Tort law

Development of constitutional tort began in India in the early 1980s.[20] It influenced the direction tort law in India took during the 1990s.[20] In recognizing state liability, constitutional tort deviates from established norms in tort law.[20] This covers custodial deaths, police atrocities, encounter killings, illegal detention and disappearances.

Property law

Trust law

Trust law in India is mainly codified in the Indian Trusts Act of 1882 which came into force on March 1, 1882. It extends to the whole of India except for the state of Jammu and Kashmir and Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

Family law

Family laws in India are different for different religions and there is no uniform civil code. This system of distinct laws for each religion began during the British Raj when Warren Hastings in 1772 created provisions prescribing Hindu law for Hindus and Islamic law for Muslims, for litigation relating to personal matters.[21] However, after independence, efforts have been made to modernise various aspects of personal law and bring about uniformity among various religions. Areas in which reform has occurred recently are custody and guardianship laws, adoption laws, succession law and laws relating to domestic violence and child marriage.

Hindu Law

As far as Hindus are concerned there is a specific branch of law known as Hindu Law. Though the attempt made by the first parliament after independence did not succeed in bringing forth a Hindu Code comprising the entire field of Hindu family law, laws could be enacted touching upon all the major areas affecting family life among Hindus in India. Even Jains are covered for most part by Hindu law.

Mohammedan law

Indian Muslims' personal laws are based on the Sharia, which is partially applied in India.[22] The portion of the fiqh applicable to Indian Muslims as personal law is termed Mohammedan law.[23] Despite being largely uncodified, Mohammedan law has the same legal status as other codified statutes.[24] The development of the law is largely on the basis of judicial precedent, which in recent times has been subject to review by the courts.[24] The contribution of Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer in the matter of interpretation of the statutory as well as personal law is significant.

Christian Law

As for Christians, there is a distinct branch of law known as Christian Law which is mostly based on specific statutes.

Christian law of Succession and Divorce in India have undergone changes in recent years. The Indian Divorce (Amendment) Act of 2001 has brought in considerable changes in the grounds available for divorce. By now Christian law in India has emerged as a separate branch of law.It covers the entire spectrum of family law so far as it concerns Christians in India. Christian law, to a great extent is based on English law but there are laws that originated on the strength of customary practices and precedents.

Christian family law has now distinct sub branches like laws on marriage, divorce,restitution, judicial separation, succession, adoption, guardianship,maintenance, custody of minor children and relevance of canon law and all that regulates familial relationship.

Nationality law

Nationality law or citizenship law is mainly codified in the constitution of India and the Citizenship Act of 1955. Although the Constitution of India bars multiple citizenship, the Parliament of India passed on January 7, 2004, a law creating a new form of very limited dual nationality called overseas citizenship of India. Overseas citizens of India will not enjoy any form of political rights or participation in the government, however, and there are no plans to issue to overseas citizens any form of Indian passport.

Law enforcement

India has a multitude of law enforcement agencies. All agencies are part of the Internal Affairs Ministry (Home Ministry). At the very basic level is the local police which is under state jurisdiction.

See also

- Central Bureau of Investigation

- Indian Penal Code

- Law enforcement in India

- Legal systems of the world

- Supreme Court of India

Notes

- ↑ http://www.commonlii.org/in/legis/num_act/

- ↑ Glenn 2000, p. 255

- ↑ Glenn 2000, p. 276

- ↑ Alexander, C.H. (July 1952). "International Law in India". The International and Comparative Law Quarterly 1 (3): 289–300. ISSN 00205893.

- ↑ Viswanatha, S.T., International Law in Ancient India, 1925

- ↑ Glenn 2000, p. 273

- ↑ Jain 2006, p. 2

- ↑ Basu 2007, p. 27

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Basu 2007, p. 41

- ↑ Basu 2007, p. 42

- ↑ Basu 2007, p. 43

- ↑ Basu 2007, p. 53

- ↑ Basu 2007, p. 50

- ↑ Basu 2007, p. 59

- ↑ Basu 2007, p. 63

- ↑ News Brief

- ↑ http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/India-decriminalises-gay-sex/articleshow/4726608.cms

- ↑ "India Country Overview 2008". World Bank. 2008. http://www.worldbank.org.in/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/COUNTRIES/SOUTHASIAEXT/INDIAEXTN/0,,contentMDK:20195738~menuPK:295591~pagePK:141137~piPK:141127~theSitePK:295584,00.html.

- ↑ "World Bank criticizes India's labor laws". http://www.siliconindia.com/shownews/World_Bank_criticizes_India%E2%80%99s_labor_laws_-nid-29498.html.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Dr. Usha Ramachandran. "Tort Law in India" (PDF). http://www.ielrc.org/content/a0206.pdf.

- ↑ Jain 2006, p. 530

- ↑ Fyzee 2008, p. 1

- ↑ Fyzee 2008, p. 2

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Fyzee 2008, p. 65

References

- Basu, Durga Das (2007). Commentary on the Constitution of India (8th ed.). Nagpur: Wadhwa & Co. ISBN 9788180384790.

- Fyzee, Asaf A.A. (2008). Outlines of Muhammadan Law (5th ed.). Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195691696.

- Glenn, H. Patrick (2000). Legal Traditions of the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198765754.

- Jain, M.P. (2006). Outlines of Indian Legal and Constitutional History (6th ed.). Nagpur: Wadhwa & Co. ISBN 9788180382642.

External links

- Indian Kanoon - Search engine for Indian laws and court judgments

- Laws of India - Source for Laws made by States in India

- Manupatra - online legal resource

- Information about Section 498a of Indian law- Section 498a

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||